The Time Team special on 1066: The Lost Battlefield aired tonight. What we now know is that the Battle of Hastings was not at Battle, nor at Caldbec Hill, nor at Crowhurst. The best guess of the Time Team guys, based on some sketchy laser mapping of just the Battle town centre, was that it might be under a traffic circle on the edge of town. Not exactly rigorous or convincing.

Of course, if you start by putting the Norman army and Harold's men in the wrong place at the start of their march that fateful day, you're not likely to find the right place for the battlefield. If the Normans were not marching from the modern town of Hastings, but from the medieval port of Hastings at Winchelsea or their camp in the Brede Valley, then the battle happened somewhere else entirely.

I feel vindicated. Hooray! I'm not such a loonie!

NEW BOOK - THE CARMEN IN FULL COLOUR!

Carmen Widonis - The First History of the Norman Conquest

Transcription, Translation and Commentary by Kathleen Tyson

Sunday, 1 December 2013

Friday, 4 October 2013

Published! Carmen de Triumpho Normannico - The Song of the Norman Conquest

Well, it's finally done. After months of painstaking effort I'm now happy enough to hit the PUBLISH button again. The book is called Carmen de Triumpho Normannico - The Song of the Norman Conquest. It is the first transcription and translation to benefit from high resolution images of the 12th century manuscript. It also has end notes on all the changes from earlier transcriptions, as well as footnotes putting the narrative of the Carmen in historical context.

I'm also publishing an English-only version titled The Song of the Norman Conquest for those who don't want the distraction of Medieval Latin with their history.

I've been much more rigorous in what is included this time around. I've taken out most of the speculative content, though some of that was very compelling and would benefit from more research. I still think there's more to the backstory of the conquest than we currently understand, but the evidence is likely to lie in archives in Paris and Rome.

The geographic clues in the Carmen are perhaps the most exciting contribution to a fuller understanding of 1066. Based on the description in the Carmen I suggest the Norman fleet landed in the estuarine Brede Valley and camped below Iham. The 'fort lately destroyed' that gets rebuilt was likely St Leonard's church on Iham, an alien cell of Fecamp Abbey for administration of the port. The battle was probably somewhere along the ridgeway roads leading from the valley. The hill might be quite modest as William (mounted) can see Harold (on foot) fighting on the summit from the ridge below, implying it was smaller than the usual candidates of Battle hill, Telham hill and Caldbec hill. A battle on the Great Ridge above Hastings or the Udimore ridge makes sense of the forces seeing each other on the march and is consistent with Harold was rushing down for a surprise attack on the Norman camp. The Roman road crossed the Rother at the limit of its tidal reach, running down to Sedlescombe at the limit of the Brede's tidal reach. But if Harold was in a hurry, which the Carmen says he was, and as he knew the area well, he might have had his forces cross the Rother below Bodiam or Northiam at low tide using makeshift pontoon bridges.

I was down in Winchelsea last weekend to speak to the Winchelsea Archeological Society about the geography of the Carmen. We got pretty excited thinking that the Normans had landed in the valley and that Harold might be buried somewhere on Iham. It was great fun talking to a roomful of people who are open to questioning the traditional assumptions about the Battle of Hastings and maybe even doing a few test trenches to see if there's something to find today.

I'm also publishing an English-only version titled The Song of the Norman Conquest for those who don't want the distraction of Medieval Latin with their history.

I've been much more rigorous in what is included this time around. I've taken out most of the speculative content, though some of that was very compelling and would benefit from more research. I still think there's more to the backstory of the conquest than we currently understand, but the evidence is likely to lie in archives in Paris and Rome.

The geographic clues in the Carmen are perhaps the most exciting contribution to a fuller understanding of 1066. Based on the description in the Carmen I suggest the Norman fleet landed in the estuarine Brede Valley and camped below Iham. The 'fort lately destroyed' that gets rebuilt was likely St Leonard's church on Iham, an alien cell of Fecamp Abbey for administration of the port. The battle was probably somewhere along the ridgeway roads leading from the valley. The hill might be quite modest as William (mounted) can see Harold (on foot) fighting on the summit from the ridge below, implying it was smaller than the usual candidates of Battle hill, Telham hill and Caldbec hill. A battle on the Great Ridge above Hastings or the Udimore ridge makes sense of the forces seeing each other on the march and is consistent with Harold was rushing down for a surprise attack on the Norman camp. The Roman road crossed the Rother at the limit of its tidal reach, running down to Sedlescombe at the limit of the Brede's tidal reach. But if Harold was in a hurry, which the Carmen says he was, and as he knew the area well, he might have had his forces cross the Rother below Bodiam or Northiam at low tide using makeshift pontoon bridges.

I was down in Winchelsea last weekend to speak to the Winchelsea Archeological Society about the geography of the Carmen. We got pretty excited thinking that the Normans had landed in the valley and that Harold might be buried somewhere on Iham. It was great fun talking to a roomful of people who are open to questioning the traditional assumptions about the Battle of Hastings and maybe even doing a few test trenches to see if there's something to find today.

Tuesday, 23 July 2013

Mea Culpa - Well, this is embarassing . . .

I've temporarily suspended the Carmen from sale for some fairly substantive revisions. Having received the digital images of the manuscript yesterday, I've been able to check those transcription sections that were particularly problematic against the manuscript.

I'm crushed to report that the agent of the City's negotiations with King William was not William the Norman, Bishop of London, celebrated for just this achievement in the City for over 700 years - until nudged aside by the mythical Ansgar the Staller. However, the agent wasn't Ansgar the Staller either, so at least I was in good company being misguided by the text. It was someone else entirely. The manuscript - clear before me - suddenly revealed the answer in a blinding flash of insight. This section of the Carmen now makes perfect sense, even without changing a word - as all the transcribers have done to make sense of the section. And I'm chagrined to admit he really did have enfeebled loins and walked slow.

I'd be gutted if I weren't so thrilled to be working with the manuscript at last. It's amazingly liberating to be free of received transcription, checking each word individually against the manuscript to ensure the accuracy of my own transcription. And the script is very beautiful. I've fallen in love with the Carmen all over again. I worked on it for 12 hours continuously yesterday, and could happily have worked all night too.

Until now I've been making emendations as infeliticies are brought to my attention, one of the benefits of publishing in print-on-demand format. That was never very satisfactory, even though each time I thought I had it finally 'right'. As I go through the manuscript I'm now also checking each word of Latin to ensure the translation suits case/declension/tense/etc. Having the manuscript to work from means I'm not imagining earlier transcription errors in compiling my transcription or translation (as I admit I did with kidney and kingdom). There may still be transcription errors in the manuscript from its copying, but that's still an improvement on using the 19th century transcriptions.

The Latin to English translation will now be much more precise. In my amateur enthusiasm I had thought conveying the sense of the text would be enough, but the Latin pedants have schooled me harshly otherwise. I'm determined to be as literal as I can get without sacrificing too much readability. I am still aiming for the popular history market rather than exclusively academic libraries, but hope to find a balance between meticulous reflection of the Latin and a melifluous cracking good read.

I'll save the answer of who saved London for another day, having learned the hard way that a bit of diligence in private is better than infelicities in the translation in public. I'll discuss it with those at the Battle Conference this weekend first to get their reactions.

In other news, I've finally received from the British inter-library loan system the only available copy of the Barlow Carmen. As I suspected, it came from the British Library. It's a good thing I'm not relying on libraries for my sales with that track record to go by. I wonder if it broke double digits. Anyway, I'm grateful to have it, and will compile a concordance of Merton & Muntz / Barlow / Tyson translations for academics that want to enquire about discrepancies between the translations. There are going to be enough to make the exercise well worth while in establishing credibility for the new translation.

For those happy or unhappy few of you who bought the Carmen between April and now, whether in Kindle or print formats, I'll exchange for a new one if you want to be updated. Drop me an email: carmenandconquest (at) gmail (dot) com. I can't say fairer than that.

I'm crushed to report that the agent of the City's negotiations with King William was not William the Norman, Bishop of London, celebrated for just this achievement in the City for over 700 years - until nudged aside by the mythical Ansgar the Staller. However, the agent wasn't Ansgar the Staller either, so at least I was in good company being misguided by the text. It was someone else entirely. The manuscript - clear before me - suddenly revealed the answer in a blinding flash of insight. This section of the Carmen now makes perfect sense, even without changing a word - as all the transcribers have done to make sense of the section. And I'm chagrined to admit he really did have enfeebled loins and walked slow.

I'd be gutted if I weren't so thrilled to be working with the manuscript at last. It's amazingly liberating to be free of received transcription, checking each word individually against the manuscript to ensure the accuracy of my own transcription. And the script is very beautiful. I've fallen in love with the Carmen all over again. I worked on it for 12 hours continuously yesterday, and could happily have worked all night too.

Until now I've been making emendations as infeliticies are brought to my attention, one of the benefits of publishing in print-on-demand format. That was never very satisfactory, even though each time I thought I had it finally 'right'. As I go through the manuscript I'm now also checking each word of Latin to ensure the translation suits case/declension/tense/etc. Having the manuscript to work from means I'm not imagining earlier transcription errors in compiling my transcription or translation (as I admit I did with kidney and kingdom). There may still be transcription errors in the manuscript from its copying, but that's still an improvement on using the 19th century transcriptions.

The Latin to English translation will now be much more precise. In my amateur enthusiasm I had thought conveying the sense of the text would be enough, but the Latin pedants have schooled me harshly otherwise. I'm determined to be as literal as I can get without sacrificing too much readability. I am still aiming for the popular history market rather than exclusively academic libraries, but hope to find a balance between meticulous reflection of the Latin and a melifluous cracking good read.

I'll save the answer of who saved London for another day, having learned the hard way that a bit of diligence in private is better than infelicities in the translation in public. I'll discuss it with those at the Battle Conference this weekend first to get their reactions.

In other news, I've finally received from the British inter-library loan system the only available copy of the Barlow Carmen. As I suspected, it came from the British Library. It's a good thing I'm not relying on libraries for my sales with that track record to go by. I wonder if it broke double digits. Anyway, I'm grateful to have it, and will compile a concordance of Merton & Muntz / Barlow / Tyson translations for academics that want to enquire about discrepancies between the translations. There are going to be enough to make the exercise well worth while in establishing credibility for the new translation.

For those happy or unhappy few of you who bought the Carmen between April and now, whether in Kindle or print formats, I'll exchange for a new one if you want to be updated. Drop me an email: carmenandconquest (at) gmail (dot) com. I can't say fairer than that.

Monday, 8 July 2013

King Offa's 790 Charter for Londonwick and Portus Hastingas et Peuenisel

London, Hastings and Pevensey may have been Frankish/Norman colonies in medieval

England, settled by Frankish colonists from 785 onwards. The burgesses of these ports described inland

England as "foreign". Hostility and tensions grew as the size and wealth of the

ports increased. Godwin sacked and seized the ports

in 1052. With London and other church lands at risk in 1066, Normandy,

France and the Roman church allied to conquer England and place William

of Normandy on the throne.

King Offa emulated Charlemagne, with whom he regularly corresponded, in developing England once he had conquered and secured the formerly tribal kingdoms into a unified realm.

Below is the charter that set the whole train of events into motion.

I’ve been trying to find the full text of the 790 charter

whereby King Offa confirmed the 785 grant of ports at Hastings, Pevensey and

Londonwick to Saint Denis for some time.

Today I finally found not one but two transcriptions of the charter in

Latin, but only partial translations to English.

Modern scholars say the charters are forged, but only based on analysis of the cartulary, not the lost original charters with seals intact. Scholars that saw the originals in the 19th century thought them real enough. It is difficult to know one way or the other, but what we can observe is the history that followed and reason whether there might be some historic basis for the Franci and the Frencisce - tribal Anglo-Normans living in coastal settlements for centuries - to concentrate in Hastings, Pevensey, London and coastal ports under their protection. Many records of battles refer to Franci and Frencisce fighting alongside Saxons to defend England from Vikings. All of this suggests there might more validity to the Saint Denis charters than is usually accorded them on the basis of philology alone.

Modern scholars say the charters are forged, but only based on analysis of the cartulary, not the lost original charters with seals intact. Scholars that saw the originals in the 19th century thought them real enough. It is difficult to know one way or the other, but what we can observe is the history that followed and reason whether there might be some historic basis for the Franci and the Frencisce - tribal Anglo-Normans living in coastal settlements for centuries - to concentrate in Hastings, Pevensey, London and coastal ports under their protection. Many records of battles refer to Franci and Frencisce fighting alongside Saxons to defend England from Vikings. All of this suggests there might more validity to the Saint Denis charters than is usually accorded them on the basis of philology alone.

Never one to shy from some fun Latin translation, I’ve

rendered my own quick and dirty translation of the 790 royal charter below. This is a fascinating document, confirming

the grant of three principal ports of early medieval England to the national church

of France. If the charters were given effect, then Hastings and Pevensey likely remained Anglo-Norman ports for more than 250 years, until taken by Godwin of Wessex - King Harold's father. London would remain Frankish influenced much longer, into the 13th century, with its independence secured by a further charter from William the Conqueror in 1066 addressed to both English and Frankish burgesses.

Why would an English king give London, Hastings and Pevensey

to France? For the care of his soul and

the stability of his kingdom, sure, but also because Saint Denis was a

commercial powerhouse and would bring the dynamic commercialism of early

medieval France and his hero Charlemagne into staid and parochial England through

profitable and efficient administration of the ports. It was the same rationale which would establish Hong Kong by treaty between China and Britain centuries later. Also, the Danes had become much more aggressive, even overwintering in England the year before, so King Offa would be highly motivated to adopt the system that Charlemagne had employed to fund and organise walled borough towns under administration of the church as strongholds against the Vikings.

King Offa emulated Charlemagne, with whom he regularly corresponded, in developing England once he had conquered and secured the formerly tribal kingdoms into a unified realm.

- He established mints that standardised the English silver penny with the like coin used in France. These coins were styled much superior to anything before or after among the Saxon kings, evidencing the immigration of Italian or French coinsmiths during Offa's reign.

- He brought in the Tribal Hideage to determine property rights, land use and taxation.

- He organised the countryside into territorial hundreds, with a borough town given to a church in every hundred to promote markets, trade and industry.

- He promoted the marriage of his sons and daughters (unsuccessfully) with the heirs of Charlemagne that the kingdoms either side of the Channel might become closer entwined through posterity.

- He endowed the Roman church in England richly with lands and commercial privileges to promote the civilising and stabilising influence of Christianity among a widely dispersed, pagan, tribal set of peoples whom he sought to govern as a single, united realm.

- He adopted Carolingian forms for diplomas and charters and used a well-crafted seal in contrast to the barbarous style of his predecessors and successors.

If the Saint-Denis charters were given effect then Hastings, Pevensey and London ports were the medieval equivalents

of Hong Kong, Singapore and Macao: colonies to be settled and run by foreigners to promote inland

trade and commercial development. Chinese

rulers could have overrun Hong Kong at any time with enough political will, but

they did not and they do not today because trade and technology are more

important than sovereignty and taxes over a few square miles of port and a few

stroppy foreigners whose departure would weaken and diminish the future

prospects of an emerging economy.

English, Franks, Normans and other ambitious settlers came

to the colonies of London, Hastings and Pevensey to set up businesses and

prosper from trading with the 'foreign' inland English from the security of the ports.

The English are referred to as 'foreign' in port documents of the day and places like Rye Foreign in East Sussex carry the distinction in their names today because Rye was a member port of Hastings. Citizens of the ports were “law-worthy” - endowed with repulican self-governance independent of manorial or king's law. The ports offered duty-free markets, just like ports and airports still do today, which made them very attractive and established the model

for ports into modern times.

Where “Londonwick” is located has been a matter of dispute. It has been placed outside the City of London’s

walls below the Strand and as far away as Sandwich, but I think it is pretty

clearly Billingsgate. London-wick literally

translates as tidal, estuarine port at London. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says Mellitus was the first bishop in Londonwick, making it clear Londonwick means London.

There is no reason to think King Offa’s

geography so bad that he couldn’t find London, and there is every reason to

expect that London then, as today, attracts many immigrants from across the Channel.

Billingsgate itself may be named for the practice of stamping duty paid on imports. Bulla means stamp or seal, such as would have been given on customed goods at the port by the port reeve who collected the taxes. There was a Bulverhythe (bull at haven) near Hastings and a Bullhythegate at Cambridge. Very likely the names evolved once from the location of customs houses at the port gates. Certainly port replaces wick in common usage at London after the 8th century, indicating a change in administration from manorial law of the king to church law. London-wick becomes London-port. The wick-reeve (vicgerefe) becomes the portreeve. Port was Frankish and Roman usage, wick was Saxon.

Billingsgate itself may be named for the practice of stamping duty paid on imports. Bulla means stamp or seal, such as would have been given on customed goods at the port by the port reeve who collected the taxes. There was a Bulverhythe (bull at haven) near Hastings and a Bullhythegate at Cambridge. Very likely the names evolved once from the location of customs houses at the port gates. Certainly port replaces wick in common usage at London after the 8th century, indicating a change in administration from manorial law of the king to church law. London-wick becomes London-port. The wick-reeve (vicgerefe) becomes the portreeve. Port was Frankish and Roman usage, wick was Saxon.

More to the point, the Benedictines of Saint Denis

would have established a church at the port of Billingsgate to administer trade at the

port. There was a church dedicated to Saint Botolph,

the first Benedictine saint of England.

There are three other churches dedicated to Saint Botolph, each outside

a principal gate of the City of London.

Very likely the commercial footprint of the monks expanded out from the

port to control all trade in and out of London, exactly as they controlled all

trade in and out of Paris. There was also a St Botolphs church at the landing gate to medieval Cambridge.

Under the early laws of Saxon England, all sales of any item exceeding a very small sum were required to be witnessed in a port by a portreeve. Also, visiting boatmen were given freedom of the port, but not allowed to venture further into English lands. For both these reasons it would be important to control access in and out of London and other major medieval ports.

Under the early laws of Saxon England, all sales of any item exceeding a very small sum were required to be witnessed in a port by a portreeve. Also, visiting boatmen were given freedom of the port, but not allowed to venture further into English lands. For both these reasons it would be important to control access in and out of London and other major medieval ports.

Why is all this important?

Because Godwin of Wessex and the young Harold hated the French and the Normans, and resented

their freedom from tax and toll as Anglo-Danish manorial overlords of Wessex. Godwin coveted their gold and their silver and

their ability to tax trade across the Channel and inland. They sacked and seized Hastings in 1052 when they raised an armed rebellion against Edward the Confessor. Godwin and Harold had also taken ports from the English church,

including Bosham from Chichester and Dover from Canterbury.

Imagine if Chairman Mao had rolled tanks into Hong Kong in

1961 and killed all the British industrialists, bankers and merchants living

there, seizing all their gold and other wealth.

Well, the French and the Normans resented violent seizure just as bitterly, and

the pope in Rome would have resented royal charters being undefended by the

sitting monarch in England. Abbot John

of Fecamp Abbey came to England in 1054 to plead with Edward the Confessor for

restoration of the ports after Godwin's death. Harold refused and Edward could not raise an army against the

powerful and popular Harold of Wessex.

As long as the French, Normans and Rome thought William,

Duke of Normandy, would succeed Edward as king, they took no action. Once half-Danish Harold, who had no noble blood, took the

crown of England, his foes across the channel allied together to conquer

England. The Frankish allies would have feared

losing London. The Normans resented

losing both the crown and the ports in Sussex belonging to Fecamp Abbey. Rome would have feared losing all of England

to a degraded Christianity approaching the former paganism, and feared the loss of wealth

and influence throughout the lands previously bestowed by more Christian

monarchs on the early church in England.

In September of 1066 a fleet set sail for England to take

the crown and restore the church’s lands.

It carried the banner of St Peter, a ring bestowed by the pope, and an edict to all the clerics of England

to support William’s claim to the throne.

The monks of Fecamp Abbey provided a boat of their own with twenty

warrior monks, a captain and very likely a harbour pilot.

King Harold brought his nobles, hauscarls and fyrd to meet the

invaders near the Sussex coast. His army

suffered defeat from fusillades of arrows and darts and alternating cavalry

charges. Harold fell. William took command of his realm. To secure the approval of London to his coronation, he granted the Frankish and English citizens of London to be law-worthy, as they were in Edward's day, with rights of inheritance. He was

crowned king with the Witenagemot's assent on Christmas Day 1066.

Below is the charter that set the whole train of events into motion.

By command of Offa, Glorious King of England:

Evident and established fact declares the frailty of human life being bound to countless daily misfortunes. Therefore anyone to keep and be master of believing repents and safeguards before he passes across the mournful void. Therefore every one of us must strive anxiously while the will of God grants we remain, lest these same be without the spiritual and just rewards when they pass away.

On which account in the name of God, I, Offa, King of Mercia, provide to Abbot Maginarius through his legate Nadelharium of land in that place at the gate known widely by the name Londonwick, where the two brothers Agonawala and Sigrinus together owned property they voluntarily willed two years ago to Saint Denis, precious martyr, who is in France. In completion of the same, I likewise surrender all my claims at law to receive tax and custom payable to myself until now retained, whether in gold or silver or other rents altogether, for the sake of love for God the all-powerful and reverence for the blessed martyrs Denis, Rusticus and Eleutherius, to the Abbot Maginarius and the holy brotherhood and their successors in the same illustrious monastery that is established in Gaul in honour of the martyr. With a devout and willing mind, together with my wife and my son, and with the consent of my nobles, from this day I concede the emergence of the muniment and I want it to be perpetual, so that from this day neither I nor my heirs, nor any earthly power may reclaim it hereafter whatever he accounts as his due nor take it back, but always in my time and even my successors in power abide by the order of the abbot and the brotherhood pleasing to Christ, that they may become greater and more perfect. In addition, our friend and faithful Duke Berhtwald and his brother Eadbald, provided a place of refuge at their property Rotherfield, which is in the county called Sussex above the river Saforda,[1] and the port above the sea of Hastingas et Peuenisel, some time past in an undertaking legally witnessed in favour of the same martyred saints petitioned in great sickness that then afflicted the duke. When he had made a recovery, the aforesaid abbot asked likewise for an undertaking. We and my noble assembly approve and confirm together.

If anyone, contrary to this strongly desired disposition to the blessed martyrs for love of God and care of our salvation detracts, infringes or dishonours these grants, a curse come upon him damning him to eternal fire. Who however protects and sustains will live with the blessing of God in perpetuity.

That this may secure full strength, each signature below affirms, as well I make my mark impressed in seal.

The year of our Lord 790, indiction 13, the 33rd year of my reign, with these witnesses, second day of Easter, three days before the ides of April, in Tamworth, this charter I confirm with a sign of the cross of Christ.

† I, Offa, king of England these gifts my hand confirms and subscribes.† Hygberht, archbishop [Lichfield] subscribes.

† Unuuona, bishop [Leicester] subscribes.

† Cynethryth, queen, subscribes.

† Ecgferth, son of the king, subscribes.

† Brorda, duke, subscribes.

† Berhtwald, duke, subscribes.

† Eodbald, duke, subscribes.

† Edwin, count, subscribes.

† I, Nedelharius, monk, with my brother Vitale and Duke Eodbald, accept this letter from the hand of the king and carry it with me into France to place above the tomb of blessed martyr Saint Denis to preserve this order forever, where the memory of the king as benefactor will be celebrated in perpetuity. Amen.

[1]

Literally Sea-ford, the river may refer to either the Rother or the Ouse, both

of which had headwaters near Rotherfield and both of which were estuarine

rivers at the time, with tideways reaching deep into Sussex that could be forded at low tide.

Wednesday, 19 June 2013

What's Wrong With the Barlow Carmen? Part II and Part III

I've now read the 1999 Barlow Carmen. Professor Barlow is generous with citations of his academic peers, the currency of academia. I can see why he was popular. His book creates an anthology of authority and academic insight about the Carmen, but he adds nothing original to the interpretation of the Latin.

Professor Barlow must have been a wonderful man and an inspirational teacher. His former students - now leading classicists and professors themselves - are very loyal. Even so, I have to believe that deference to academic precedent and received authority, without recognition that much of it was fanciful, are not the best way to gain an insight into the Carmen or tell its story.

Five hours with the Barlow Carmen at the British Library was enough to convince me that I have not wasted my time in re-translating the Carmen. I am sure I have made many mistakes in my translation. My Latin is not perfect and I am an inexperienced translator, but at least I am doing the work myself - and I make corrections as I recognise my errors. I don't accept received translation errors, or cling to errors I have made rather than emending them to more accurately reflect the original text.

The things I considered inaccurate in the M&M Carmen were all there repeated in the Barlow Carmen:

- William is among the four who kill Harold;

- The army is at Canterbury for a month rather than Dover;

- A dude with a bad kidney and game leg ruled London.

Here's Barlow on the most important lines in dispute, lines 681-688:

No way does the Latin say this. It doesn't even make sense. How could "the city's business" be "done" with the aid of itinerant and ignorant provincial staller? Why would the aldermen and portreeve tolerate his sudden interference? Where was the Witanagemot, which had appointed Edgar to be king of the City, in allowing the staller to usurp authority over the City? How could a rural staller be an expert on urban defenses? Why would the City's citizens take orders from a wounded, incontinent interloper? None of this makes any sense, either in the context of the Carmen or in the context of known history about the medieval administration of the City of London.

This is silliness, and that it is persistent silliness that has endured since the first transcriptions makes it more unfortunate but not more credible. In 1066 you might eat a kidney from an animal, but you would be unlikely to diagnose a kidney complaint in a living human. To think anyone would be diagnosed and then described in text as having "kidney trouble" is far-fetched. At that time you were much more likely to be described as "elf shot" if you had a mysterious, debilitating condition.

I have now written to the Royal Library of Belgium to ask for a digital photograph of the relevant lines of the manuscript. I want to know once and for all whether the word is renum - kidney - or regnum - kingdom. Even if the word on the vellum is renum, as indicated by my 1837 and 1840 transcriptions, that doesn't change my view that regnum was intended. It would, however, establish whether the transcription error occured in the 12th century when the Brussels Carmen was copied by some cleric, or in the 19th century when the manuscript Carmen was transcribed into modern text.

Worse than the received translation is the determination to justify it. There is no record of any Ansgar having any authority in 1066 London. There are no documents which identify this mythical ruler of the weak kidney and war wounds. That hasn't stopped Barlow and others looking around for any Ansgar they could find and transplanting him to London, and even interlacing his name in the Carmen in the English narrative out of context. There was only one Ansgar they could identify, a Sussex staller, and so they say he must have travelled to London to lead the revolt there after receiving his wounds at Hastings.

This mythologising is inconsistent with everything we know about London in 1066. London in 1066, like London today, was a corporate jurisdiction ruled by its burgesses (citizens) through elected aldermen. Its most important officials were the bishop of London and the portreeve: the bishop for its sacred offices and the portreeve for the secular administration and taxation of commerce.

Ansgar the staller ruling London is even inconsistent with the Carmen itself, which makes clear that London's great men rule it by consensus and democratic voting. The Carmen describes their deliberations and records their votes, not once but twice. First it describes their deliberation and voting to open negotiations with King William on the basis of the 1066 charter. Second it describes their deliberations and voting to approve his coronation as king.

It seems obvious to me that Ansgardus is a corruption of Edgar. London did have a king in 1066, and the Carmen would name the boy king. As there is no other name for the boy king mentioned in the Carmen, it must be Ansgardus. Also, the Latin makes perfect sense both times the name is used if it references the boy king. More telling still, line 726 says Quicquid ab Ansgardo nuncius attulerat - whatever the envoy brought from Edgar. Envoys are always characterised by the authority of the ruler they speak for, and since London had a king, only the king could send an envoy to William.

My Carmen is supported by a much closer alignment between Latin and English, known facts and contemporary documents as well as common sense. William is turned from razing London and subjugating its citizenry by a bishop's disclosure of the church of Rome's protection of the City as a livery port originally ceded by King Offa to St Denis in 790. There is plenty of factual support for this interpretation:

184 years of silliness is enough. It is time the Carmen was given meaning that makes sense in the context of real history and not made up fantasy.

Earlier post: What's Wrong With the Barlow Carmen?

Update: What's Wrong With the Barlow Carmen? Part III (9 July 2013)

It just isn't publicly available! I've been waiting four weeks for an inter-library loan of a Barlow Carmen through my local library. The email came Friday advising it was ready to collect. It wasn't. They said come back Tuesday as the emails sometimes go ahead of the books. So I went again today.

It's not the Barlow Carmen. It's Morton and Muntz again. Despite my carefully specifying Barlow's name as translator and the OMT ISBN number for the 1999 edition, they could only get a Morton and Muntz 1972 Carmen. Instead of "kidney trouble" the dude who rules London at line 682 is "crippled by a weakness of the loins".

This is hugely irritating as I was planning to complete a line by line comparison of my translation to Barlow's before the Battle Conference in two weeks' time.

Well, at least the British Library is reasonably convenient. I've ordered the Barlow Carmen (offsite storage so 48 hours delay!) to be available in the reading room Thursday morning. I'll take my laptop and transcribe it onsite.

The Carmen is a consitutional original source document about the creation of England as a Christian nation in Europe. It is unconscionable that it should be so difficult for the public to get a look at it.

Did I mention my Carmen is available globally? And affordable? 'Nuf said.

Professor Barlow must have been a wonderful man and an inspirational teacher. His former students - now leading classicists and professors themselves - are very loyal. Even so, I have to believe that deference to academic precedent and received authority, without recognition that much of it was fanciful, are not the best way to gain an insight into the Carmen or tell its story.

Five hours with the Barlow Carmen at the British Library was enough to convince me that I have not wasted my time in re-translating the Carmen. I am sure I have made many mistakes in my translation. My Latin is not perfect and I am an inexperienced translator, but at least I am doing the work myself - and I make corrections as I recognise my errors. I don't accept received translation errors, or cling to errors I have made rather than emending them to more accurately reflect the original text.

The things I considered inaccurate in the M&M Carmen were all there repeated in the Barlow Carmen:

- William is among the four who kill Harold;

- The army is at Canterbury for a month rather than Dover;

- A dude with a bad kidney and game leg ruled London.

Here's Barlow on the most important lines in dispute, lines 681-688:

In the city was a man, crippled by kidney trouble and hampered in his walk because he had suffered many wounds while serving his country. As he lacked mobility he was carried in a litter; but it was he ruled over the city fathers and it was with his help that the city's business was done. To this man the king, through an envoy, covertly unveiled another way out, and secretly asked to view it with favour.

No way does the Latin say this. It doesn't even make sense. How could "the city's business" be "done" with the aid of itinerant and ignorant provincial staller? Why would the aldermen and portreeve tolerate his sudden interference? Where was the Witanagemot, which had appointed Edgar to be king of the City, in allowing the staller to usurp authority over the City? How could a rural staller be an expert on urban defenses? Why would the City's citizens take orders from a wounded, incontinent interloper? None of this makes any sense, either in the context of the Carmen or in the context of known history about the medieval administration of the City of London.

This is silliness, and that it is persistent silliness that has endured since the first transcriptions makes it more unfortunate but not more credible. In 1066 you might eat a kidney from an animal, but you would be unlikely to diagnose a kidney complaint in a living human. To think anyone would be diagnosed and then described in text as having "kidney trouble" is far-fetched. At that time you were much more likely to be described as "elf shot" if you had a mysterious, debilitating condition.

I have now written to the Royal Library of Belgium to ask for a digital photograph of the relevant lines of the manuscript. I want to know once and for all whether the word is renum - kidney - or regnum - kingdom. Even if the word on the vellum is renum, as indicated by my 1837 and 1840 transcriptions, that doesn't change my view that regnum was intended. It would, however, establish whether the transcription error occured in the 12th century when the Brussels Carmen was copied by some cleric, or in the 19th century when the manuscript Carmen was transcribed into modern text.

Worse than the received translation is the determination to justify it. There is no record of any Ansgar having any authority in 1066 London. There are no documents which identify this mythical ruler of the weak kidney and war wounds. That hasn't stopped Barlow and others looking around for any Ansgar they could find and transplanting him to London, and even interlacing his name in the Carmen in the English narrative out of context. There was only one Ansgar they could identify, a Sussex staller, and so they say he must have travelled to London to lead the revolt there after receiving his wounds at Hastings.

This mythologising is inconsistent with everything we know about London in 1066. London in 1066, like London today, was a corporate jurisdiction ruled by its burgesses (citizens) through elected aldermen. Its most important officials were the bishop of London and the portreeve: the bishop for its sacred offices and the portreeve for the secular administration and taxation of commerce.

Ansgar the staller ruling London is even inconsistent with the Carmen itself, which makes clear that London's great men rule it by consensus and democratic voting. The Carmen describes their deliberations and records their votes, not once but twice. First it describes their deliberation and voting to open negotiations with King William on the basis of the 1066 charter. Second it describes their deliberations and voting to approve his coronation as king.

It seems obvious to me that Ansgardus is a corruption of Edgar. London did have a king in 1066, and the Carmen would name the boy king. As there is no other name for the boy king mentioned in the Carmen, it must be Ansgardus. Also, the Latin makes perfect sense both times the name is used if it references the boy king. More telling still, line 726 says Quicquid ab Ansgardo nuncius attulerat - whatever the envoy brought from Edgar. Envoys are always characterised by the authority of the ruler they speak for, and since London had a king, only the king could send an envoy to William.

My Carmen is supported by a much closer alignment between Latin and English, known facts and contemporary documents as well as common sense. William is turned from razing London and subjugating its citizenry by a bishop's disclosure of the church of Rome's protection of the City as a livery port originally ceded by King Offa to St Denis in 790. There is plenty of factual support for this interpretation:

- William the Norman was bishop of London in 1066. With a name like that, he might have been nervous about having an anti-Norman king with a history of genocides in church port liveries ruling England.

- Saint-Denis dominated all international trade between Paris and all other medieval ports from the 7th century onwards, building itself into a huge monopoly on trade that rivalled anything Rome had achieved under the era of empire. Saint-Denis was the most influential church in France, where all but two French kings are buried. King William would no more thwart Saint-Denis than he would the pope;

- Saint-Denis cartularies include copies of the King Offa 790 port livery charter that endowed port liveries at Londonwick, Hastings and Pevensey to the Abbey of Saint-Denis along with generous immunities and privileges in connection with trade and commerce, and later royal charters by later Saxon kings that confirmed the port liveries up to the time of Edward the Confessor;

- Duke William had sworn to restore the church liveries seized by Godwin of Wessex and the young Harold before setting out for England, as recorded at Steyning in respect of Fecamp Abbey liveries, so ceding London to Saint-Denis would be entirely consistent with his known respect for church liveries, especially those belonging to French and Norman churches;

- It was customary in medieval England - and medieval France too - to allow civil (as opposed to feudal) government in church livery boroughs, with burgesses/citizens electing aldermen on democratic principles, and independent laws and courts;

- The Corporation of London retains the 1066 charter for London which accords with my interpretation of the Carmen. The 1066 charter is addressed to William, the bishop of London, Godfrey, the portreeve, and the burgesses of London - both French and English. Addressing Frankish (or more accurately Anglo-Norman) citizens of London indicates that trade and emigration from France were significant drivers of the City's prosperity, which would be expected after 24 years of Edward the Confessor's pro-Norman administration. The charter assures the Frankish and English citizens of London that they will remain "law-worthy" - meaning they can make and enforce their own laws, consistent with urban civil rule in both France and England;

- In 1067 King William restored Hastings, Rye, Old Winchelsea, the Manor of Rameslie (including the port at Petit Iham), and Steyning to Fecamp Abbey in a royal charter that cited earlier charters of Edward and his Saxon predecessors, confirming the importance of the livery ports seized by Godwin and Harold as a casus belli for the conquest and demonstrating William's determination to generously provide for the church as king of England.

184 years of silliness is enough. It is time the Carmen was given meaning that makes sense in the context of real history and not made up fantasy.

Earlier post: What's Wrong With the Barlow Carmen?

Update: What's Wrong With the Barlow Carmen? Part III (9 July 2013)

It just isn't publicly available! I've been waiting four weeks for an inter-library loan of a Barlow Carmen through my local library. The email came Friday advising it was ready to collect. It wasn't. They said come back Tuesday as the emails sometimes go ahead of the books. So I went again today.

It's not the Barlow Carmen. It's Morton and Muntz again. Despite my carefully specifying Barlow's name as translator and the OMT ISBN number for the 1999 edition, they could only get a Morton and Muntz 1972 Carmen. Instead of "kidney trouble" the dude who rules London at line 682 is "crippled by a weakness of the loins".

This is hugely irritating as I was planning to complete a line by line comparison of my translation to Barlow's before the Battle Conference in two weeks' time.

Well, at least the British Library is reasonably convenient. I've ordered the Barlow Carmen (offsite storage so 48 hours delay!) to be available in the reading room Thursday morning. I'll take my laptop and transcribe it onsite.

The Carmen is a consitutional original source document about the creation of England as a Christian nation in Europe. It is unconscionable that it should be so difficult for the public to get a look at it.

Did I mention my Carmen is available globally? And affordable? 'Nuf said.

Wednesday, 5 June 2013

Lanfranc - A very unhappy archbishop of Canterbury!

I came across a 1070 letter of Lanfranc of Pavia (prior of Bec, next abbot of Caen, then archbishop of Canterbury from 1070) to Pope Alexander II, and had no sooner started reading it than I was hooting with laughter. It's a pure joy to read, despite it expressing the unhappiness of poor Lanfranc at finding himself beset among the brutish, pagan and near-pagan English against his will.

Here it is, from Lanfranci Opera, J.A. Giles (1844):

Whatever his misgivings about his qualifications or temperment, Lanfranc proved an efficient and conscientious administrator. He rebuilt Canterbury Cathedral, which burnt down on his arrival in England. He placed one of his proteges in St Albans where the grand St Albans Cathedral soon grew as a centre for learning. Both were erected by the same architect and craftsmen, using Caen stone imported from Normandy. Lanfranc oversaw the reformation of the English church to bring it in line with Rome's orthodoxy, placing Norman prelates in charge of bishoprics and abbeys throughout England.

Despite his cares of office, Lanfranc would outlive his former student. Alexander II died in 1073. Lanfranc would remain archbishop of Canterbury until his death in 1089. His death removed the last constraint on the ill-natured William Rufus, King William II, who then fell out with the Church and brought chaos on the realm as the wily Lanfranc had much earlier predicted.

Here it is, from Lanfranci Opera, J.A. Giles (1844):

To Pope Alexander, the chief shepherd of holy Church, Lanfranc, an unworthy prelate, canonical obedience. I know no one, holy father, to whom I can with greater propriety unfold my troubles than to you, who are the cause of these calamities. For when William, duke of Normandy, drew me forth from the monastery of Le Bec where I had assumed the religious habit, and appointed me to preside over that of Caen, I found myself unequal to the task of governing a few monks. Therefore I cannot comprehend by what dispensastion of the Almighty I have been promoted at your behest to undertake the supervision of an innumberable mulititude. The aforesaid prince, after he had become king of England, tried every means to bring this about, but laboured in vain until your legates, Ermenfrid, bishop of Sitten, and Hubert, cardinal of the holy Roman Church, came to Normandy, caused the bishops, abbots and magnates of that land to be assembled, and in their presence and by virtue of the authority of the apostolic see commanded me to undertake the government of the church of Canterbury. Against this I pleaded in vain my incapacity and unworthiness, my ignorance of the language and of the barbarous people. My plea did not avail. What need of further words! I gave my consent, I came, I took the burden upon me, and such are the cares and troubles, the discomfort of mind I daily endure, so great are the annoyance, the suffering, the losses caused me by different persons pulling me in opposite directions, the harshness, avarice and baseness that I see around me; so dire is the peril to which in my view holy Church is exposed, that I grow weary of my life, and lament that it has been prolonged to witness such times. But bad as is the present state of things when I look around me, I feel the future will be still worse. That I may not detain your highness, whose time must be fully occupied with other weighty matters, longer than is necessary - since it was beyond dispute by your authority that I became charged with these duties - I entreat you in God's name and for the sake of your own soul, by the same authority to release me from them and grant me leave to return once more to the monastic life I love above all other. Do not, I pray, spurn this my petition, for I only ask what is right and necessary to my well-being. You should remember, and indeed never forget, how ready I have always been to entertain in my monastery your kinsfolk and others who came bearing letters of introduction from Rome. I instructed them in both sacred and secular learning as well as I was able to teach or they to learn; and many other things I might mention in which I have been of service to you or your predecessors when time or circumstances allowed. My conscience bears witness that I do not say this boastfully or by way of reproach, or to obtain favours from you beyond what is due to my obedience. My sole object in writing this letter is to put forward a just and valid reason why for Christ's sake I should obtain the favour I am seeking at your hands. If, however, you should be guided by the interests of others and decide to refuse my request, it is greatly to be feared you may run the risk - which God forbid - of committing a sin by the very act you consider well-pleasing to God. For I have met with no spiritual success in these parts either directly or indirectly, or, if any, it is so slight that it cannot possibly be weighed against my misfortunes. But enough of this for the present. When I was at Rome and by God's grace had the pleasure of seeing you and conversing with you, you invited me to visit you again the following year at Christmas and to spend three or four months in your palace as your guest. But God is my witness, and the angels, that I could not do so without great personal inconvenience and to the detriment of my affairs. For this there are many different reasons, too long to be related in a short letter; but, should the heavenly powers preserve my life circumstances permit, I long to visit you and the shrine of the holy apostles and the holy Roman Church. To this end I entreat you to pray the divine mercy that long life may be granted to my lord the king of England and peace from all his enemies. May his heart ever be moved by love for God and holy Church with all devotion of spirit. For while he lives we enjoy peace of a kind, but after his death we may scarcely hope to experience either peace or any manner of good.I can't help wondering if Pope Alexander II had the same reaction I did when he read this, and envision him rolling about on crimson cushions laughing at the trials of the ever-insolent and insubordinate Lanfranc.

Whatever his misgivings about his qualifications or temperment, Lanfranc proved an efficient and conscientious administrator. He rebuilt Canterbury Cathedral, which burnt down on his arrival in England. He placed one of his proteges in St Albans where the grand St Albans Cathedral soon grew as a centre for learning. Both were erected by the same architect and craftsmen, using Caen stone imported from Normandy. Lanfranc oversaw the reformation of the English church to bring it in line with Rome's orthodoxy, placing Norman prelates in charge of bishoprics and abbeys throughout England.

Despite his cares of office, Lanfranc would outlive his former student. Alexander II died in 1073. Lanfranc would remain archbishop of Canterbury until his death in 1089. His death removed the last constraint on the ill-natured William Rufus, King William II, who then fell out with the Church and brought chaos on the realm as the wily Lanfranc had much earlier predicted.

Friday, 10 May 2013

Who killed King Harold at the Battle of Hastings?

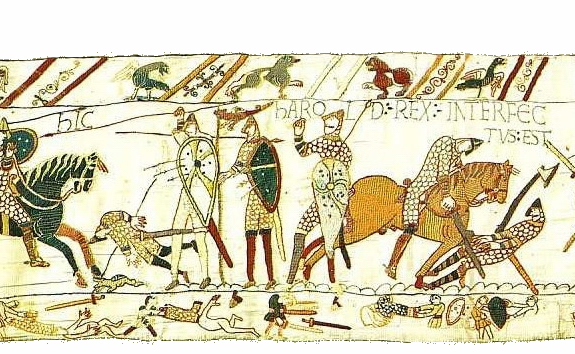

This scene from the Carmen is the one that most interests popular historians. The death of King Harold is described from line 533 to line 554.

Each of the four plays a role in the death, so that King Harold falls to lance, sword, pike and axe.

The death of Harold was already in dispute in 1067, as the Carmen's composer notes at line 542, so he would have been cautious in writing a record of the battle that he then hoped would be read throughout the world.

It seems likely quite a mob of allied cavalry responded to the duke's summons for an assault on the summit. The resulting melee may have been variously reported.

Guy d'Amiens may have been anticipating other claims for the credit of killing King Harold. The story of an arrow striking down the king first emerges from Amatus of Monte Cassino in 1080. The Italian archers at the Battle of Hastings may have wanted credit for the famous victory.

Certainly the archers and crossbowmen were critical in overwhelming the superior numbers of Saxons in the shield wall and fyrd. Their pikes, swords and axes, and even their spears, would have been ineffectual against allied artillery firing at them all through the morning, as described in the Carmen, decimating their ranks from a safe distance. The terror of death raining down on them while they stood helpless must have been maddening. Saxons had never confronted crossbow bolts before, capable of piercing their shields and chainmail. Even the Norman arrows were steel tipped and barbed for maximum penetration and damage, and they had spent all year manufacturing sufficient arms for the attack. Having provided the strategic advantage which assured victory for the Normans, the allied archers from Italy may have sought credit for the death of King Harold as well.

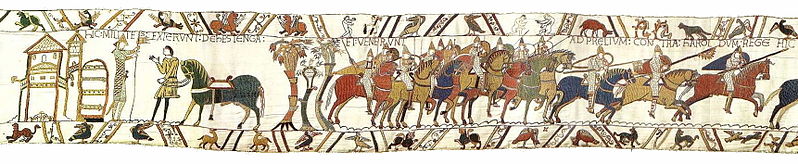

The Bayeux Tapestry does not clarify things much here. There are two figures potentially identified as Harold in the scene titled "Here King Harold is killed".

One might have an arrow in his eye, although it is suggested this was added later. The other is being cut down by a knight, and possibly having his leg cut off. The Carmen would support the later image as being King Harold. The Carmen depicts Harold as fighting bravely to the last.

Interesting to note the French already stripping the dead of anything of value in the lower margin of the Tapestry, again consistent with the narrative of the Carmen.

535.

Advocat Eustachium liquens ibi praelia Francis,

The duke summons Eustace from the Franks then clearing the field,

536.

Oppressis validum contulit auxilium.

He musters strong aid for the oppressed.

537.

Alter ut Hectorides Pontivi nobilis heres,

Like a second Hector, the noble

heir of Ponthieu,

538.

Hos comitatur Hugo promptus in officio.

Hugh accompanies these, ever ready for duty.

539.

Quartus Gilfardus patris a cognomine dictus.

Fourth is Gilfard, called by his father’s surname.

540.

Regis ad exicium quatuor arma ferunt.

The four come armed to overwhelm the king.

Each of the four plays a role in the death, so that King Harold falls to lance, sword, pike and axe.

The death of Harold was already in dispute in 1067, as the Carmen's composer notes at line 542, so he would have been cautious in writing a record of the battle that he then hoped would be read throughout the world.

It seems likely quite a mob of allied cavalry responded to the duke's summons for an assault on the summit. The resulting melee may have been variously reported.

Guy d'Amiens may have been anticipating other claims for the credit of killing King Harold. The story of an arrow striking down the king first emerges from Amatus of Monte Cassino in 1080. The Italian archers at the Battle of Hastings may have wanted credit for the famous victory.

Certainly the archers and crossbowmen were critical in overwhelming the superior numbers of Saxons in the shield wall and fyrd. Their pikes, swords and axes, and even their spears, would have been ineffectual against allied artillery firing at them all through the morning, as described in the Carmen, decimating their ranks from a safe distance. The terror of death raining down on them while they stood helpless must have been maddening. Saxons had never confronted crossbow bolts before, capable of piercing their shields and chainmail. Even the Norman arrows were steel tipped and barbed for maximum penetration and damage, and they had spent all year manufacturing sufficient arms for the attack. Having provided the strategic advantage which assured victory for the Normans, the allied archers from Italy may have sought credit for the death of King Harold as well.

The Bayeux Tapestry does not clarify things much here. There are two figures potentially identified as Harold in the scene titled "Here King Harold is killed".

One might have an arrow in his eye, although it is suggested this was added later. The other is being cut down by a knight, and possibly having his leg cut off. The Carmen would support the later image as being King Harold. The Carmen depicts Harold as fighting bravely to the last.

Interesting to note the French already stripping the dead of anything of value in the lower margin of the Tapestry, again consistent with the narrative of the Carmen.

Saturday, 4 May 2013

A medieval data standard? The Carmen suggests a Barony Naming Convention

A lot of the globalisation of financial markets has been driven by the implementation of global data standards so that computers can talk to each other in the same language around the world. I've been involved in developing these data standards for international payments and securities markets for almost 20 years. As a result, I am perhaps more sensitive to data standards than many.

Perhaps that is why I am drawn to Latin. Latin was a global Roman-era and medieval data standard for globally consistent communications. Anyone speaking or writing Latin could communicate with anyone else speaking or writing Latin throughout the Roman Empire or the Catholic Church.

When I first read through the Carmen in Latin portus ab antiquis Vimaci - the ancient port of Vimeu - at line 48 leapt out at me, as I had already read somewhere that the Norman invasion fleet departed from St Valery-sur-Somme, at the mouth of the Somme River. Indeed, the description of the port in the Carmen said that the Abbey of Saint Valery overlooked the port and that it was at the mouth of the Somme, so there could be no mistake.

So what or where was Vimaci? Why was the name Vimaci used by the Guy d'Amiens writing the Carmen instead of the name of the port, despite his being otherwise very economical in his text?

Vimeu is not a port or even a town. It was a medieval barony. The medieval barony spread inland from the coast of the Somme covering a pretty large area. As soon as I saw this, I thought <barony naming convention/>!

The cleric who wrote the Carmen adopted a convention of ignoring local place names in favour of referencing the barony associated with the local place and supplementing the barony name with locally descriptive features. If this was true for Guy d'Amiens, it might be true for other medieval clerics as well.

A barony naming convention would explain why the Normans called it the Battle of Hastings instead of naming it for the battlefield. The battle took place in the Rape (barony) of Hastings on land that was subject to Hastings' jurisdiction. The Saxons called it the Battle of Senlac according to Orderic Vitalis, after the local name of the place. Senlac means "sandy loch" and would fit the wide, sandy Brede Valley flood plain through which the estuarine Brede River meandered.

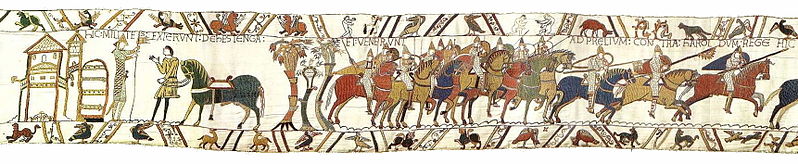

A barony naming convention would explain why the makers of the Bayeux Tapestry wrote that the fleet sailed for Pevensey if it landed in the valley. The ports of Brede and Petit Iham were limbs of Pevensey, owing the service of ships, men and boys to the League of Pevensey each year for fixed terms.

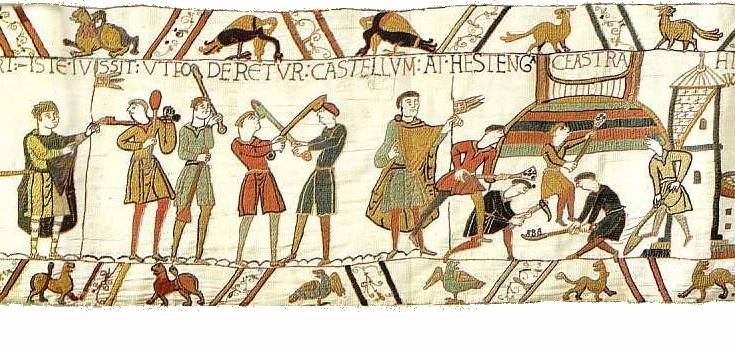

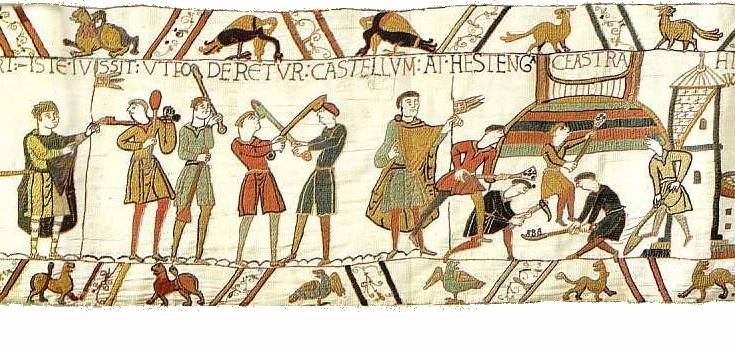

A barony naming convention would explain why the raiding parties went to loot Hastings though it is clear from the pictures in the tapestry - and particularly the depiction of the boats with open oar ports - that the camp was some remote distance from Hastings along the coast.

A barony naming convention would explain why the makers of the Bayeux Tapestry wrote that the a motte was erected at the Hastings camp. Iham Hill was a parish in the jurisdiction of medieval Hastingas, probably going back to the original 790 King Offa charter giving Hastings, Pevensey, Londonwick and other ports and trade privileges to the Abbey of Saint-Denis. The camp of the invasion force was in the Rape of Hastings.

The same barony naming convention would explain why the army marched from Hastings to go to battle. If the building shown is the rebuilt "fortress lately razed" of St Leonard's Church on Iham Hill, then it makes sense. St Leonard's was a parish of Hastings, in the Rape of Hastings.

Hastinga being sacked is clearly different to Hastinga Ceastra where they have camped, and both look different to the fortified place from which the army marches. If they are all named Hastings because of a Barony Naming Convention, then these diverse scenes of the Bayeux Tapestry which seem to imply three different places may finally make sense.

I am not enough of a medieval scholar to know whether others have detected the use of a barony naming convention before in other medieval clerical works, but I am very keen to find out!

Perhaps that is why I am drawn to Latin. Latin was a global Roman-era and medieval data standard for globally consistent communications. Anyone speaking or writing Latin could communicate with anyone else speaking or writing Latin throughout the Roman Empire or the Catholic Church.

When I first read through the Carmen in Latin portus ab antiquis Vimaci - the ancient port of Vimeu - at line 48 leapt out at me, as I had already read somewhere that the Norman invasion fleet departed from St Valery-sur-Somme, at the mouth of the Somme River. Indeed, the description of the port in the Carmen said that the Abbey of Saint Valery overlooked the port and that it was at the mouth of the Somme, so there could be no mistake.

So what or where was Vimaci? Why was the name Vimaci used by the Guy d'Amiens writing the Carmen instead of the name of the port, despite his being otherwise very economical in his text?

Vimeu is not a port or even a town. It was a medieval barony. The medieval barony spread inland from the coast of the Somme covering a pretty large area. As soon as I saw this, I thought <barony naming convention/>!

The cleric who wrote the Carmen adopted a convention of ignoring local place names in favour of referencing the barony associated with the local place and supplementing the barony name with locally descriptive features. If this was true for Guy d'Amiens, it might be true for other medieval clerics as well.

A barony naming convention would explain why the Normans called it the Battle of Hastings instead of naming it for the battlefield. The battle took place in the Rape (barony) of Hastings on land that was subject to Hastings' jurisdiction. The Saxons called it the Battle of Senlac according to Orderic Vitalis, after the local name of the place. Senlac means "sandy loch" and would fit the wide, sandy Brede Valley flood plain through which the estuarine Brede River meandered.

A barony naming convention would explain why the makers of the Bayeux Tapestry wrote that the fleet sailed for Pevensey if it landed in the valley. The ports of Brede and Petit Iham were limbs of Pevensey, owing the service of ships, men and boys to the League of Pevensey each year for fixed terms.

| 38 | HIC WILLELM[US] DUX IN MAGNO NAVIGIO MARE TRANSIVIT ET VENIT AD PEVENESAE | Here Duke William in a great fleet crossed the sea and came to Pevensey |

A barony naming convention would explain why the raiding parties went to loot Hastings though it is clear from the pictures in the tapestry - and particularly the depiction of the boats with open oar ports - that the camp was some remote distance from Hastings along the coast.

| 40 | ET HIC MILITES FESTINAVERUNT HESTINGA UT CIBUM RAPERENTUR | and here the knights have hurried to Hastings to seize food |

A barony naming convention would explain why the makers of the Bayeux Tapestry wrote that the a motte was erected at the Hastings camp. Iham Hill was a parish in the jurisdiction of medieval Hastingas, probably going back to the original 790 King Offa charter giving Hastings, Pevensey, Londonwick and other ports and trade privileges to the Abbey of Saint-Denis. The camp of the invasion force was in the Rape of Hastings.

| 45 | ISTE JUSSIT UT FODERETUR CASTELLUM AT HESTENGA CEASTRA | He ordered that a motte should be dug at Hastings Camp | |

The same barony naming convention would explain why the army marched from Hastings to go to battle. If the building shown is the rebuilt "fortress lately razed" of St Leonard's Church on Iham Hill, then it makes sense. St Leonard's was a parish of Hastings, in the Rape of Hastings.

| 48 | HIC MILITES EXIERUNT DE HESTENGA ET VENERUNT AD PR[O]ELIUM CONTRA HAROLDUM REGE[M] | Here the knights have left Hastings and have come to the battle against King Harold |

Hastinga being sacked is clearly different to Hastinga Ceastra where they have camped, and both look different to the fortified place from which the army marches. If they are all named Hastings because of a Barony Naming Convention, then these diverse scenes of the Bayeux Tapestry which seem to imply three different places may finally make sense.

I am not enough of a medieval scholar to know whether others have detected the use of a barony naming convention before in other medieval clerical works, but I am very keen to find out!

Sunday, 28 April 2013

What's wrong with the Barlow Carmen?

The short answer to the title question is I don't know what's wrong with the Barlow Carmen. I haven't seen the Barlow Carmen. It costs over £100 on Amazon and isn't available from any public lending library in southeast England. I might have been able to obtain it on inter-library loan from the British Library, but I am not a scholar and didn't want it for research. I wanted a Carmen to read for personal enjoyment. I wanted a Carmen to understand the contemporaneous Norman story of the events of the conquest as they unfolded in 1066.

Now that I have produced my own English translation of the Carmen, those familiar with the Barlow Carmen ask why I bothered. The question has been raised five times in three months, so here is the answer: temporary insanity.

I never intended to translate the Carmen before actually doing so. I took possession of the only English translation Carmen I could obtain (the 1972 Morton & Muntz Carmen) from my local library on 25th January, having waited three weeks for the single copy available in southeast England. Within days the Carmen took possession of me.

It is an indictment of the academic press that the Carmen is so hard to get and so expensive. Every schoolchild in Britain should know about the Carmen as a thrilling story of blood, plunder and conquest that shaped world history. Every English historian should have a copy as a fundamental reference work for the Norman Conquest. Although if they were exposed to the M&M version, they might not find the story either gripping or credible. Right away I began to see problems with the translation.

I started translating a few lines myself, one or two at a time, and the more I did, the more obsessive I became. There is so much more in the Carmen than appeared in the English. I stopped reading the English.

I found the original transcription of the Carmen published in Rouen in 1840 and another transcription from 1869. I transcribed the Carmen in Latin from beginning to end on my computer, and then began translating it from line 1 to line 835. When I finished I went back and re-translated for sense and context. The Latin is so elegant that if the English jarred or seemed disruptive then I knew that I had missed something. Where the Latin didn't make sense, I checked all the transcriptions for possible errors and made sensible corrections of my own. I kept doing this obsessively for three months, sometimes 20 hours a day. My son became frightened when he started coming home from school to find me still hunched over the keyboard in my jammies, not having bothered to eat, brush my teeth or feed the cats. If anyone doubts the originality of my efforts, I have plenty of translations of incrementally improving quality to prove that I did the work.

Why is my Carmen worth reading? First, it's a cracking good story of blood, plunder and conquest - as its author intended it to be. Second, it costs £100 less than the Barlow Carmen. If you want a Carmen that reads well and doesn't put you in debt, mine is a sensible choice. Third, my Carmen is available worldwide instantly as an ebook, where the Barlow Carmen is almost entirely unavailable to the public except to scholars with access to specialist libraries or people who can drop £100 on a book. Finally, and perhaps most important, my Carmen is free of received translation and therefore probably truer to the original Latin. I'll let others compare the texts, but I know for certain that I reveal significant new facts about the Norman Conquest while still translating the Carmen word for word from the original.

It is important that the history the Carmen reveals about the Norman Conquest be better understood and more widely available.

What's wrong with the Barlow Carmen? It isn't publicly available.

Now that I have produced my own English translation of the Carmen, those familiar with the Barlow Carmen ask why I bothered. The question has been raised five times in three months, so here is the answer: temporary insanity.

I never intended to translate the Carmen before actually doing so. I took possession of the only English translation Carmen I could obtain (the 1972 Morton & Muntz Carmen) from my local library on 25th January, having waited three weeks for the single copy available in southeast England. Within days the Carmen took possession of me.

It is an indictment of the academic press that the Carmen is so hard to get and so expensive. Every schoolchild in Britain should know about the Carmen as a thrilling story of blood, plunder and conquest that shaped world history. Every English historian should have a copy as a fundamental reference work for the Norman Conquest. Although if they were exposed to the M&M version, they might not find the story either gripping or credible. Right away I began to see problems with the translation.

I started translating a few lines myself, one or two at a time, and the more I did, the more obsessive I became. There is so much more in the Carmen than appeared in the English. I stopped reading the English.

I found the original transcription of the Carmen published in Rouen in 1840 and another transcription from 1869. I transcribed the Carmen in Latin from beginning to end on my computer, and then began translating it from line 1 to line 835. When I finished I went back and re-translated for sense and context. The Latin is so elegant that if the English jarred or seemed disruptive then I knew that I had missed something. Where the Latin didn't make sense, I checked all the transcriptions for possible errors and made sensible corrections of my own. I kept doing this obsessively for three months, sometimes 20 hours a day. My son became frightened when he started coming home from school to find me still hunched over the keyboard in my jammies, not having bothered to eat, brush my teeth or feed the cats. If anyone doubts the originality of my efforts, I have plenty of translations of incrementally improving quality to prove that I did the work.

Why is my Carmen worth reading? First, it's a cracking good story of blood, plunder and conquest - as its author intended it to be. Second, it costs £100 less than the Barlow Carmen. If you want a Carmen that reads well and doesn't put you in debt, mine is a sensible choice. Third, my Carmen is available worldwide instantly as an ebook, where the Barlow Carmen is almost entirely unavailable to the public except to scholars with access to specialist libraries or people who can drop £100 on a book. Finally, and perhaps most important, my Carmen is free of received translation and therefore probably truer to the original Latin. I'll let others compare the texts, but I know for certain that I reveal significant new facts about the Norman Conquest while still translating the Carmen word for word from the original.

It is important that the history the Carmen reveals about the Norman Conquest be better understood and more widely available.

What's wrong with the Barlow Carmen? It isn't publicly available.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)