535.

Advocat Eustachium liquens ibi praelia Francis,

The duke summons Eustace from the Franks then clearing the field,

536.

Oppressis validum contulit auxilium.

He musters strong aid for the oppressed.

537.

Alter ut Hectorides Pontivi nobilis heres,

Like a second Hector, the noble

heir of Ponthieu,

538.

Hos comitatur Hugo promptus in officio.

Hugh accompanies these, ever ready for duty.

539.

Quartus Gilfardus patris a cognomine dictus.

Fourth is Gilfard, called by his father’s surname.

540.

Regis ad exicium quatuor arma ferunt.

The four come armed to overwhelm the king.

Each of the four plays a role in the death, so that King Harold falls to lance, sword, pike and axe.

The death of Harold was already in dispute in 1067, as the Carmen's composer notes at line 542, so he would have been cautious in writing a record of the battle that he then hoped would be read throughout the world.

It seems likely quite a mob of allied cavalry responded to the duke's summons for an assault on the summit. The resulting melee may have been variously reported.

Guy d'Amiens may have been anticipating other claims for the credit of killing King Harold. The story of an arrow striking down the king first emerges from Amatus of Monte Cassino in 1080. The Italian archers at the Battle of Hastings may have wanted credit for the famous victory.

Certainly the archers and crossbowmen were critical in overwhelming the superior numbers of Saxons in the shield wall and fyrd. Their pikes, swords and axes, and even their spears, would have been ineffectual against allied artillery firing at them all through the morning, as described in the Carmen, decimating their ranks from a safe distance. The terror of death raining down on them while they stood helpless must have been maddening. Saxons had never confronted crossbow bolts before, capable of piercing their shields and chainmail. Even the Norman arrows were steel tipped and barbed for maximum penetration and damage, and they had spent all year manufacturing sufficient arms for the attack. Having provided the strategic advantage which assured victory for the Normans, the allied archers from Italy may have sought credit for the death of King Harold as well.

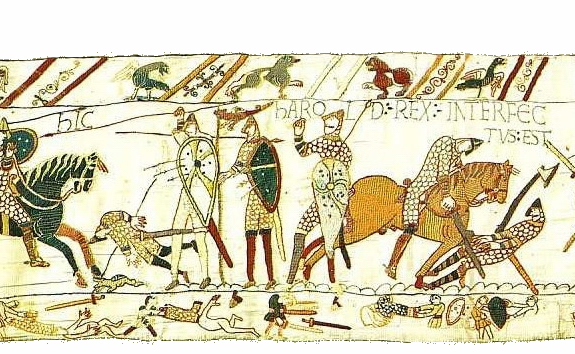

The Bayeux Tapestry does not clarify things much here. There are two figures potentially identified as Harold in the scene titled "Here King Harold is killed".

One might have an arrow in his eye, although it is suggested this was added later. The other is being cut down by a knight, and possibly having his leg cut off. The Carmen would support the later image as being King Harold. The Carmen depicts Harold as fighting bravely to the last.

Interesting to note the French already stripping the dead of anything of value in the lower margin of the Tapestry, again consistent with the narrative of the Carmen.

Warfare is a fascinating subject. Despite the dubious morality of using violence to achieve personal or political aims. It remains that conflict has been used to do just that throughout recorded history.

ReplyDeleteYour article is very well done, a good read.